I’m the only metalhead I know who subscribes to The New Yorker magazine, though I’m sure there are other metalhead subscribers out there. But probably not many. I usually read the movie and book reviews because the writing is so good, even though I almost never get around to reading the books or seeing the movies themselves. Most weeks, that’s all I can manage to do, usually because I don’t have the time to read more.

Sasha Frere-Jones is the magazine’s pop-music critic (though what he writes about is really more eclectic than the term “pop” might lead you to believe). He’s also a member of bands called Calvinist and Piñata. I usually read his stuff, too, but not because I have much interest in the music he covers; again, I admire the writing.

Today, the on-line version of The New Yorker published a Frere-Jones piece that I read because, for a change, I was interested in the subject matter as much as the writing. The subject is American black metal, with a particular focus on Wolves in the Throne Room and Liturgy. I found it amusing because it’s being written for an audience that probably knows nothing, or next-to-nothing, about black metal, and reading it is like seeing our tiny, extreme genre of music through someone else’s eyes.

Also, remarkably, it doesn’t use the words “fuck”, “fucking”, “brutal”, “pummeling”, or other words most of us are used to seeing (or in my case, using) in descriptions of metal. You can read the article via this link, or you can go past the jump, because I’ve pasted it into this post.

The Dark Arts

How to approach black metal.

by Sasha Frere-Jones

OCTOBER 10, 201

The fertile and fractious U.S. scene in the genre known as black metal can be understood through a familiar moment in rock history. In the sixties, British bands like Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones mined American blues, first copying their heroes and then creating something vivid and novel. In the nineties, a range of American acts began drawing from the work of Norwegian metal bands that were famous mostly for a look and for several unpleasant events. The Norwegians were largely faithful to the “corpse paint” costume, in which the face is covered in white makeup, with black circles drawn around the eye sockets. Upside-down-cross pendants and spiked bracelets were common accessories. The tabloid-worthy events centered on a musician named Varg Vikernes, of the one-man band Burzum, who encouraged and participated in the burning of churches. In 1993, while playing bass in a band called Mayhem, he murdered the guitarist, a man known as Euronymous.

Until recently, it was a legacy that the genre couldn’t shake. But now American bands such as Liturgy, Krallice, Absu, Leviathan, Wolves in the Throne Room, and Inquisition have left a fair amount of the pageantry behind—not to mention the violence—and helped to create a community, as well as a musical moment that is rife with activity. Because of what the music does formally, there is little chance that we will see a Top Ten black-metal act. The elements of the genre that are common to its bands—even those which don’t subscribe to the term, since black metal’s borders are fiercely policed—are extremely fast strumming of guitars, equally fast drumming, and singing that is either extremely low and almost gastric or very high and vaguely spectral. The vocals in the lower register have been called both “the Cookie Monster thing” and “reptilian.” The most accelerated version of the black-metal beat—in which cymbals and multiple drums are hit with the rapid and even force of a sewing machine, which almost erases the idea of drumming as time-keeping—is called the “blast beat,” which Liturgy has modified into a variable-speed approach called the “burst beat.”

This is all extreme stuff, and, when it’s played by grown men who look like couture pandas, there is plenty of reason to be skeptical. Get past the novelty, though, and you find a level of passion and an attention to detail that make a number of mere rock bands look lazy. People are starting to pay attention. Liturgy, whose members live in Brooklyn, records for the respected indie-rock label Thrill Jockey, which made its name in the mid-nineties releasing avant-garde but civilized rock. Because so many varieties of electronic and non-Western music have been tapped by traditionally organized rock bands, there is great allure in the lesser-known strategies of black metal, which was for years a self-sufficient, distinct subgenre that wasn’t looking to expand.

Liturgy’s second album, “Aesthetica,” has been widely and positively reviewed, and the band recently played at MOMA, with a film of Joseph Beuys preparing an installation as a backdrop. But success in those terms leads to backlash. Most black-metal fans would not only reject that kind of fine-art credential; they would punish a band thus associated, and Liturgy has recently been caught up in a fight about identity, the limits of pretentiousness, and the point of black metal itself. Look online for an essay called “Transcendental Black Metal,” by Hunter Hunt-Hendrix, Liturgy’s front man, and you will find the beginning of a very heated thread that addresses both “Transilvanian Hunger” and the “haptic void.” The genre and its fans are easily mocked, but the energy flowing through these arguments is bracing—and the music is growing increasingly powerful and unpredictable.

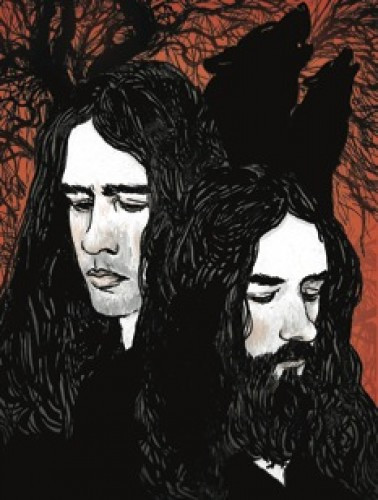

Another American group that has adapted black metal to its own ends is Wolves in the Throne Room, led by two brothers, the drummer Aaron Weaver and the guitarist Nathan Weaver, from Olympia, Washington. The band doesn’t identify itself as black metal, but, like Liturgy, it often accelerates its music to the point of blurring, where what is very loud and fast turns, in a kind of trompe-l’oreille, into something that sounds steady and comforting, like a version of medieval plainsong. Pushed to the limits of the players and their gear, this version of black metal begins to make good on some of its grandiose claims. Many of its adherents are almost monklike in their attempts to achieve “transcendence,” or, in the case of the Wolves, to agitate on behalf of sustainable farming. The quickest way to understand the newest wave of black metal is to imagine that Satan did not score a visa and is still stuck in Norway. (There are some American bands that do believe in Satanism—the scene’s factionalism underlines its fervency.)

At a recent show at the Bell House, in Brooklyn, Wolves in the Throne Room played last on a strong bill that began with Krallice. For the Wolves set, the band was partially obscured by a cloud of artificial smoke, and the stage was littered with candles and oil lanterns. Like most of their peers, the Weaver brothers, along with their additional guitarist, Kody Keyworth, don’t move around much onstage, perhaps because the physical demands of playing rule it out. The band’s new album, “Celestial Lineage,” is a nice bridge between the traditional modes of black metal and the Weaver brothers’ own concerns.

Like many black-metal bands from around the world, the Wolves have a symmetrical and entirely illegible logo that looks like a thicket of branches. The album art is moody and dark, per requirements, though a touch less ominous-looking than what you find on many other covers: what might be a couch under a sheet sits in the middle of a forest rendered in shades of light green and brown. There is no blood.

Songs like “Thuja Magus Imperium” work in lengthy, sustained melodic figures that would not sound out of place in some modern classical music. But then everything switches on, and Nathan Weaver sings in a strangled tone that is somewhere between the high, almost avian sound that Liturgy’s Hunt-Hendrix makes and the classic black-metal growl of a traditional Norwegian black-metal singer like Immortal’s Abbath Doom Occulta, as on 1992’s “The Call of the Wintermoon.”

Despite their protestations, Wolves in the Throne Room are engaged in the larger project of black metal, whose intensity makes an infinite amount of sense, whether or not you like the idea of words that you can’t possibly discern without a lyric sheet. If you’re going out of the house to hear amplified music, why not take that to its logical end? You may eventually find a TV that is sufficiently large that it makes going to a movie theatre pointless, but you are never going to replicate anything like a black-metal show at home, no matter how fancy your stereo is. The ritual aspects of makeup, smoke, and unusual typography help everyone leave the quotidian realm faster. There were moments in the Wolves set that were harmonically astonishing, when the strummed guitars felt more like the sound of massed voices, and when Nathan Weaver’s voice came across like some kind of electronic texture.

I kept thinking of Janet Cardiff ’s 2001 installation “The Forty-Part Motet,” currently playing at MOMA PS1. Cardiff re-created the performance of a forty-member choir, each singer emerging through a separate speaker, performing the 1573 Thomas Tallis piece “Spem in alium.” In eleven minutes, it uses a stunning variety of overlapping, interlocking parts, as deft in its repetition as anything Steve Reich has done. The interplay of the voices is also moving—I have rarely visited the work and not seen people crying within minutes.

“Death to false metal!” is a phrase that has circulated through various metal communities for years, often presented as a knowing joke, an acknowledgment that the seriousness of the project is rarely recognized by the mainstream. But if you’re going to be mocked for looking funny or singing in an odd voice, better to do it in the service of something verifiably remarkable.”

I have “liked” the MetalSucks page on facebook, and they posted this link a couple days along with the statement “Please tell Sasha Frere-Jones to stop writing about metal.” This confused me, because I thought it was a pretty good article.

I don’t want to get off topic, but does anyone else think MetalSucks is overly sarcastic/caustic/judgmental at times, or am I the only one?

I missed that link. I actually appreciated the fact that a publication like The New Yorker would show some attention to black metal, even if what’s in the piece could be subjected to some nit-picking, and as I said in the post, I think Frere-Jones is a very good writer. I’d like to see the “mainstream” press pay more serious attention to metal, not less — especially because most mainstream attention to metal is uninformed, ridiculously critical, and.or downright insulting.

As for MetalSucks, they were one of the inspirations for this site, and I continue to be entertained and informed by what I read there. Their style definitely tends toward the sarcastic, caustic, and judgmental (though certainly not everything they post can fairly be called that), which is also true of most stand-up comics I like. It’s part of their shtick, and I don’t put them down for that, but it’s not my style or the style of the other people who write for NCS. Different strokes for different folks.

The Washington Post wrote a really good article about grindcore and death metal that centered on Pig Destroyer, and was actually pretty sympathetic towards extreme metal. I was very pleased (I don’t know if you’ve seen it already, but: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/07/31/AR2009073102026.html

It honestly never occurred to me that the sarcasm was part of their schtick (and I agree, not everything they post is in that vein). Perhaps I should not take it so seriously, then. 😛

That’s a great article. I linked to it here:

https://www.nocleansinging.com/2011/06/05/pig-destroyer-to-play-two-shows-in-the-pacific-northwest/

And as for MetalSucks, I don’t know Vince or Axl, so calling it their shtick is more of a guess than anything based on direct knowledge about the workings of their minds.

I was trying to comment, but the internet here at work is being lame. I couldn’t remember who else has done articles like this, but Black Shuck mentioned the Washington Post’s article on Pig Destroyer. Not sure if that’s the one I was thinking of, but I think there have been a few other unexpected articles on metal bands over the past few years or so in newspapers and magazines whose normal coverage doesn’t usually come near the pit.

Who knows, maybe in time metal will get more decent coverage like this. NPR has picked up the gauntlet as of late. Why should they be the only ones? Besides, an outsider’s view (if they remain objective enough about it) can be rather enlightening for fans and musicians alike.

As for MS, I’m not sure when to take their stuff seriously and when not to, something which I think is applicable to anyone who writes for them on a regular basis. There’s a lot of sarcasm there and many of their posts are trolling and/or backhanded compliments. Personally, I think the overall quality of what Axl and Vince do at MS has declined a bit, not to mention some of what others have posted. I used to go to MS and Blabbermouth on a nearly daily basis. Now, NCS and DMB are usually the first music sites I hit, then MS if there’s nothing on the first couple pages or so that I haven’t already looked at.

Your mention of NPR is right on point. The first time I noticed that NPR was covering metal was when they included live video of Portal on the NPR site, and I nearly fell out of my chair when I saw it. Since then (and maybe before then), they’ve been doing it pretty regularly, which I think is great. Unlike people who honestly think metal needs to stay underground, I’d like to see the music (and the bands) get the broadest exposure possible.

I’m not a big follower of NPR, but I know they’ve featured metal and other music that might otherwise go unnoticed by a large part of their audience for a while. Reading their recent article on Cormorant, they also seem to have people that are familiar with metal and the bands they cover. That might not always be the case, but based on whatI have seen/read/heard with NPR, they try to put in the effort so that the end result is an informed one.

I think that having different sources can help some of these bands greatly. Metal sites generally attract a certain kind of audience, one that can turn other people away. Hell, even having Scion get involved with stuff is an interesting move, one that I wouldn’t have expected from a car manufacturer. But looking at all they have to offer, from music (a fair amount of metal, at that) to film to art and more, Scion A/V has been impressive.

The way things work today, exposure is a premium. Whether it’s NPR, Scion A/V or articles in respected print sources, the more that gets out there, the better the odds of a band (or whoever, looking at other media) getting noticed by someone.

I’ve seen people on the net slagging Scion A/V and the bands involved with their metal promotions — the whole corporate-involvement-equals-false-metal thing. But I don’t buy that argument. I suppose I’m too greedy for all the great free EPs they’ve been releasing. 🙂

Looking at the list of bands at the site, that’s a lot of well respected bands that have sold out or whatever the fuck the argument may be. In the end, it comes down to reaching an audience. If guys from a car company want to help promote these bands and get them on the road or get new tunes to their fans, more power to them. With so many bands struggling to keep the books in the black, I would think that any help would be appreciated. Doesn’t make them any less metal, doesn’t mean they’ve sold out, doesn’t make them corporate bands. It means they have an opportunity they might not otherwise have.

I suppose the same knuckledraggers could say the same shit about bands that get covered by anyone other than a zine creator who does everything by hand and uses the public library to make copies of the finished product.

Back to Scion A/V… I haven’t looked at everything they have on their site, but you’d have to go to the About Us page to see mention of cars. They also have a partners section, but the site isn’t a glaring ad trying to get people to buy stuff. I dunno, it seems that they my have fairly generous hands-off approach to the content they offer. It’s not like having bands like 1349, Wormrot, Acrassicauda, Immolation, Anaal Nathrakh or Absu (among many others) is a great marketing tool for them. Maybe they do it because they give a shit.

Whatever their motivation, someone there has got good taste in metal. I guess, like you, I’m more interested in the positive results of the project than in whether someone inside the company is convinced there’s a way to turn it into additional car sales.

To be honest, it’s not like they are one of the world’s most recognized car manufacturers or anything. Not like if it said ‘Presented by Ford Motor Company’ or something. If you saw that name and logo and were not already familiar with the company, would you know what they did? Or even that they weren’t just a segment of an entertainment PR company? Not unless you really dug into it. But if you just followed links to download the Wormrot or Enslaved EP and then went on with your business, they are getting zero publicity for themselves.

And personally, while (like Islander said) I appreciate the free music more than I’d complain about corporate involvement, that appreciation doesn’t extend toward thinking their vehicles are any less retarded-looking. So I really don’t see what they stand to gain from all this. But again, to the bands, any exposure > no exposure.

I’d just like to say that I agree with everything you guys have said about Scion.

As long as the bands don’t make any musical or lyrical changes, I don’t give a shit who pays for it. I like free music, and I like that corporations are doing something fucking POSITIVE instead of just trying to rip people off.

I’m not sure I’d ever BUY a Scion (who wants to drive a goddamn milk carton??) but, if nothing else, I really appreciate that they’re helping out such great bands. (I love Wormrot.)

Fascinating how you feel abou this writing style. I cant the help but feel it is somewhat…detached. i supposed thats a bit on purpose, since this is more or less an “outsiders” take on black metal (the reader being the outsider, not necessarily him). However, I came across another article by him in a roundabout way where he describes “The death of hip hop” which really rubbed me the wrong way. I dont like throwing around the words “classist” or “elitist” because that shit has heavy and explicit connotations. I also dont know anything bout the guy other than a few articles I’ve read. All I have is the gut feeling: people I know who talk like this are the same people who give charities to africa while ignoring the ghetto a few blocks away, the same people who have doormen that tell me “deliveries are roound back” when Im visiting a friend. Or maybe I just have a natural distrust for men named “Sasha”.

I think our friend Cosmo Lee is far mor effective. Though he is well educated and thouroughly embedded in metal subculture, he can make the most obscure and music and technical concepts instantly relatable and interesting. He can be high brow without sticking his nose up, and he can simplify things without going to the lowest common denomenator or pandering. Or, maybe I just have an affinity for people named Cosmo.

If I do one day actually get into writing seriously I will take pointers from both writers. Taking note of what I Ilike and dislike aout them equally and use it as a guideline for what and what not to do. I guess that’s ultimately the best reason to read different/dissenting opinions; if you only read people who feel the same as you, you stagnate and wont develop your own distinct voice. That said, thanks for linking that, and im glad you are willing to share your thoughts on this.

Here’s my feeling about this: There are lots of different writing styles, and no one correct way of writing. In part, what’s “right” depends on the context. The way Frere-Jones writes suits the style of The New Yorker, and it’s reflected in the tone of just about everything in the magazine. It’s what most of The New Yorker’s readers expect and want. In a way, it’s similar to the kind of English spoken on BBC news broadcasts (I understand there’s a standard way of speaking that all the news readers must use). I appreciate it for what it is, though I think it would go over like a lead balloon if used in a metal blog.

I agree that Cosmo Lee’s style is a good parallel within the world of metal. He’s an intelligent writer, and a careful one, and I also find what he writes to be interesting and informative, though I also know people who don’t enjoy his style. Course, that’s true of every writer.

I couldn’t emulate Sasha Frere-Jones or Cosmo Lee if I wanted to, but like you, I think reading good writing, no matter the style, is one way of getting better as a writer. Ultimately, though, you have to be yourself and find a style that suits who you are.

Urgh, I wish, I wish that less attention was given to the modern-art approach of bands like Liturgy and (to a lesser extent, but still) WITTR.

Seriously, “the “blast beat,” which Liturgy has modified into a variable-speed approach called the “burst beat.” – bullshit.

Sigh, it’s just all so self-aware and semi-ironic. So different to bands really throwing themselves into the music.

Honestly, I know it’s become “cool” to do so, but I legitimately HATE the shit that Litrugy peddle as “transcendental black metal”.

I think we see eye-to-eye about Liturgy and Hunter Hunt-Hendrix:

https://www.nocleansinging.com/2009/12/15/black-metal-navel-gazing/#comments

I do like the Wolves quite a bit though. Tremendous experience listening to them live.

Much as I applaud the New Yorker for ‘expanding their horizons’, the whole article comes off as pretentious and condescending IMO. I realize that’s kind of the New Yorker’s oeuvre, but still. The impression I got was “while played by ignorant savages, this ‘black metal music’ is not without its primitive charm”.

Fair point. I guess there is a whiff of condescension in tha article. I guess I’m just used to thinking of myself as an ignorant savage and therefore didn’t notice. Also, I was mesmerized by the fact that he didn’t use the word “fucking”.

I concur Troll, you stated these feelings more concisely than I in my previous. While there is value in understanding the merit of a persons writing style, one can only take so much before it pisses you off. It reminds me of when my friend gave me a Solomon Kane tales collection by Robert E. Howard. The stories were fantastic, but it was so extremely fucking difficult to get past the obscene racism, like that story with the african warrior fighting a gorilla; shit made me cringe.

Lots of good things have already been said, but I wanted to add a question from a communal point of view.

I’m not a black metal fan really, though I do appreciate its rawness. But it falls under the heading of our beloved extreme metal, so I feel slightly qualified to ask.

How so we feel about being defined by an interloper (I use the word purely for dramatic effect)?

In this article, the author seems to be making a point of differentiating the not-crazy American black metal from the crazy European metal, as if we should be ashamed of those roots. The legitimization of extreme metal, he seems to imply, can only come when we divide ourselves from the “childish” (my word) corpse paint and blind fury of Scandinavian bands.

Maybe the bands he discusses would agree with that.

But do we want to accept this definition of superior, “intellectual” metal divorced from the madness that try originally inspired it?

Personally, I don’t.

The piece functions well as an introduction to a minor group of American black metal bands who seem to revile their very genre. Which is fine with me, but I am wary of anyone e’er holding that up ad the exemplar of the genre.

I mean, WITTR try to discourage moshing and they seem to be obsessed with “transcendence”.

simply by writing only about this group, he trivializes their forebearers. (Though he also explicitly does so in the pool piece.) That is primarily what I take issue with. The piece is an introduction as much as an attempt (perhaps accidentally) at definition.

I have a feeling I shouldn’t have written this on my phone.

I don’t want to see the separation of the two, but I got into extreme metal through the crazy European stuff and am also not really a fan of Liturgy and WITTR’s “transcendental” music, so I’m not the most objective judge.

I wonder what it is about Liturgy and WITTR that makes their brand of black metal acceptable to the author, because his implication seems to be that until bands like Liturgy came along, black metal was entirely “childish”, as you put it. That might, might be true for some of the early bands (Mayhem’s “Deathcrush” had “no fun” printed on it, something that I still can’t accept was meant in seriousness), and yes, the fan base can get a little silly, especially when Liturgy is involved, but there are plenty of black metal bands that play serious metal music without devolving into into the comic, in my opinion and that of (I assume) other black metal fans (I would even call Watain and Funeral Mist “transcendental”, just not in the way that these USBM bands are). But apparently not in the author’s Is it the fact that these American bands don’t use corpsepaint? Something different they do muscially? The fact that they’re not Satanic?

That’s an excellent question, and I would guess that there are two things:

1) they’re American. I’m just guessing here, but being the home grown variety of a foreign “thing” seems to legitimize it’s artistic integrity. I guess…???

2) Lack of corpse paint and having clear “aims” probably also make the USBM bands more accessible…

Now you’ve got me second-guessing myself for saying anything nice about this article. That bit about “Satan not scoring a visa and being stuck in Norway,” while a clever way of distinguishing WITTR and Liturgy from the Norwegian forebears, also backhands the forebears. I think you’re right that he’s trivializing European BM, which sucks.

He also may make people who aren’t familiar with WITTR think they’re either tame or pretentious, and they’re neither.

Also, I just left a Seattle club after watching Agalloch. Fucking AWE. SOME.

Also, fuck-fuck-fuckity-fuck-fuck-cock-tits-scatmuncher-horse-raper-BALLS.

I don’t think it was a BAD article. But I don’t really think it was successful at what it was trying to do: act as an introduction to black metal. I mean the title wasn’t specific, it literally said: “How to approach black metal.” But it didn’t do that at all. It described a tiny subset of USBM, while literally scoffing at the genre’s roots.

Is he a dick for doing so? Not at all. But he did have the choice of leaving the progenitors alone while simply discussing the topic he clearly wanted to discuss. I think he chose the right bands to discuss for the audience of the New Yorker (and I mean that with ZERO disdain). I can’t think of any bands that I would allow me to name drop the MOMA twice in one article, and I think that kind of cultural comparison is imperative when bringing outsider art to a conventional artistic establishment. Those within the establishment (rightly) expect some barometer with which to judge the new work.

So, I think he set out what to do (make a tiny group of USBM understandable for the artistic establishment), but I don’t think he was right in holding up this one group as the end-all-be-all of black metal.

Also, fuck-fuck-fuckity-fuck-fuck-cock-tits-scatmuncher-horse-raper-BALLS.

It’s always interesting when major publications actually take any metal seriously. I remember back in, maybe, 1991 when the conservative (and for that matter best written) Swedish daily SvD ran a three page story in their weekend section about this new fangled thing called “death metal”. It was as always very well written, featuring among others Entombed and Morbid Angel, and it was to a certain extent probably a bit pretentious.

I guess my point is that I (and certainly subscribers of the New Yorker) expect a certain level or writing from such publications. While we might find their writing pretentious, I think if they changed their style for an article on black metal that would be even more so.

I didn’t have a problem with the writing style. I thought it was well written and better for it, but I disagreed with the very lopsided portrayal of black metal.

My first thought was, I thought the blast-beat-as-sewing-machine analogy was a very interesting and astute observation.

I might have looked at the overall tone of the article differently than some of you, but I didn’t get a sense of USBM as serious music for adults when ties with the Norwegian silliness are severed. I sort of thought the historical perspective was brought up as sort of preempting the readers’ potential dismissal of this subject matter. As in, unfortunately, if the general public has any awareness at all of black metal, it is probably entirely centered around the storied antics of Burzum/Mayhem/Emperor/etc., but the scene is not only defined by that time period and those events. I didn’t feel that the author was claiming this article’s subjects were worthy of being written about because they had distanced themselves from the beliefs and actions of their European counterparts, so much as he was just informing the reader (who, again, might know nothing of black metal beyond some burnt churches) that there might be some redeeming value- some art, even- if you look beneath the surface a bit.

Of course, the title was a little unfortunate and misleading, as Phro points out. A brief study on (essentially) two bands in one country is hardly any sort of grand primer on the whole entire concept. Besides, I don’t really see how an article like this would – or could – serve as an introduction to black metal for someone who’d never heard it. I don’t anticipate that the average reader will run out and buy Celestial Lineage or whatever, and start praising it as fine art. At least, I hope not. It frightens me to think of a bunch of stuffy art museum snobs suddenly appreciating any form of extreme metal simply because somebody told them they should (and not out of a real, actual appreciation for the music). It might be a stereotype, but I often think people praise many forms of modern art (paintings, sculpture, drama, etc.) that they don’t honestly enjoy or understand, just because they feel like they SHOULD like it. I’d hate to see that sort of pretension carried over to something that I truly do enjoy.

Just my opinion, but I think we’re a long way from any on-metalheads liking black metal (or any kine of extreme music) because they think they should like it, in order to prove their sophistication. On the other hand, I think there are definitely metalheads out there who profess to like certain bands in order to prove their sophistication (or maybe their “trveness”.

Well yeah, there’s that, too. Bugs me just as much, and for pretty much the same reasons. Anybody who cares enough about what other people think, that they’d either pretend to like or pretend not to like something, based on how these views are accepted by other people… people like that are pretty much just a waste of space. Get your own damn opinions, live your own damn life. But of course that’s a completely different subject, getting off topic from this article… (well, sort of).