photo by Shane Mayer

(We are thrilled to present Comrade Aleks’ interview of metal journalist David Gehlke — because it’s such a great discussion with such an experienced, articulate, and humble documenter of metal history. The ultimate focus is his new fully authorized biography of Chuck Schuldiner published by Decibel Books, but the conversation delves into many of Gehlke’s other important works as well.)

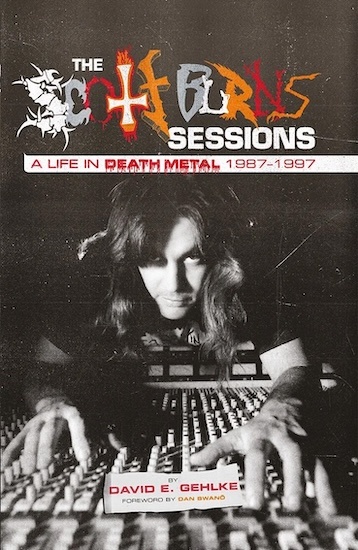

David E. Gehlke has been researching the metal underground and its suburban vicinities since 2002, and if you’re old enough, then you may have read his publications in Throat Culture, Snaggletooth and Metal Maniacs. Nowadays he’s better known for his collaboration with Dead Rhetoric and Blabbermouth as well as being the author of a few books. The titles of Damn the Machine – The Story of Noise Records and The Scott Burns Sessions – A Life in Death Metal speak for themselves, and the biographies of Paradise Lost and Obituary were something that needed to be written.

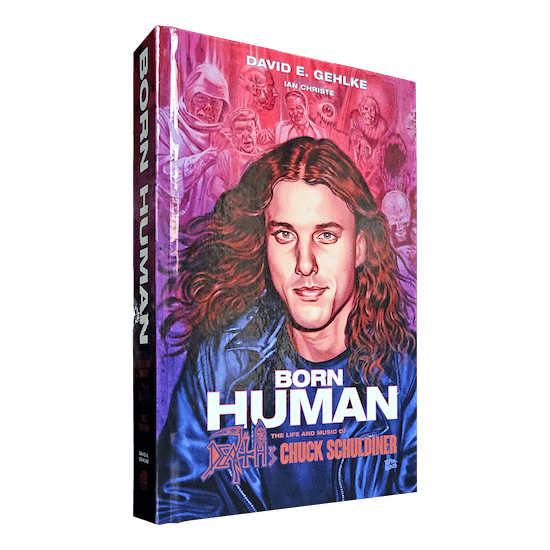

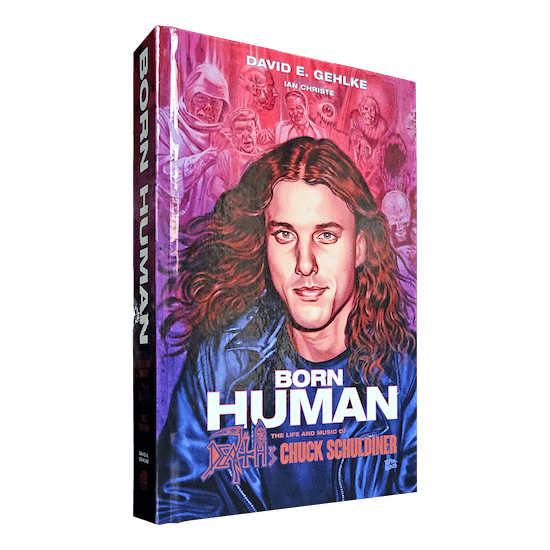

David keeps a good creative pace, and this year he released the authorized biography of Death’s founder – Born Human: The Life and Music of Chuck Schuldiner. We have prepared an extensive interview with David, so without wasting any time, I invite you to join our conversation.

David, you started your career as a metal journalist at 19 years old. I wonder if there are any journalists in this field with some special education, and if it means that you move on following the trial and error method. How much time did it take before you understood that you started to write properly?

I always enjoyed writing as a teenager and ended up going to college for it, which definitely helped when I wanted to break into the metal scene. I’m sure there are other metal journalists with similar backgrounds—I don’t think my story is particularly unique. We all have to start somewhere!

My first “gig” was with a Colorado-based magazine called Throat Culture. I’m not sure how I found them, although it may have been through the ‘zine column in Metal Maniacs magazine. Either way, I sent the editor a letter of interest, and he sent me a stack of CDs to review. It was an exciting moment when they arrived—no joke. I became a regular contributor to the magazine, then connected with several webzines and became hooked on writing about metal. (Let’s not underestimate the thrill of getting free CDs. Circa early 2000s, that was incredible!) Honestly, my goal in my 20s was to write as much about metal as I could. I was eager to dedicate myself to it and was lucky enough to meet some great people along the way.

How much did your career change since then? Do you feel that you almost reached its peak and, moreover, do you still have inner resources to enjoy new music, as its flow never ends?

I probably enjoy metal more than ever, actually. That’s the cool thing about it—you are likely to never run out of bands to discover as long as you remain involved in the scene. The debate on whether the scene is better or worse than it was in the ’80s, ’90s or 2000s could go on for days, but it’s probably more important to appreciate the fact that there is such a wealth of bands to get into—no matter the time period.

The business of writing about metal has definitely changed. Record labels are no longer as willing to fly writers around the world to cover their bands and it’s fair to reason that because of the internet, the influence of metal journalists has waned. The average listener has more resources to discover new music (for free, in most cases) and an even larger number of bands to choose from.

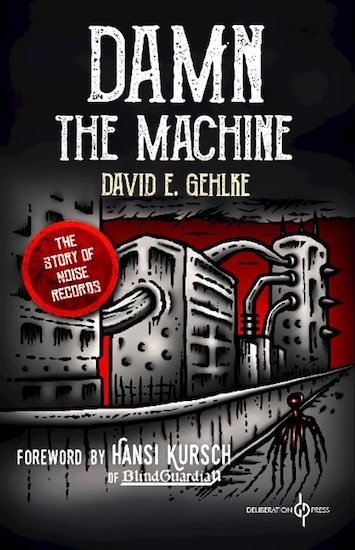

Your first book Damn the Machine tells the story of Noise Records, a label with history and legacy – no doubt. I, as a metal fan, am interested in everything regarding metal scene machinery, starting from recording and producing and ending with distribution of the final product. Yet it’s not a topic for everyone, so were you sure that the book would find its readers? Did this first release surpass your expectations in a context of feedback and some, maybe professional, recognition?

The catalyst for the Noise book was Thomas Gabriel Fischer’s 2000 book, Are You Morbid? Into the Pandemonium of Celtic Frost. Tom, of course, is a legendary musician, but he’s also an incredible writer. I probably read his book in just a few days—I couldn’t put it down. The adversary throughout Tom’s book was the owner and founder of Noise, Karl-Ulrich Walterbach. Tom was unsparing toward Karl and it became one of the key takeaways from the book: How could a small, independent metal record company have such an adversarial relationship with one of its bands?

Later, I learned that Karl had a similarly difficult relationship with other Noise bands. That, to me, was a recipe for a compelling book. The book was also strengthened by the fact that many of Noise’s top-tier bands are still active and doing quite well, especially in Europe. I’m incredibly grateful for the response to the Noise book. I had no idea what to expect, yet it continues to sell, and I still get emails from people wanting to talk about it. Now that I’m between books, I’ve started revising Damn the Machine since there are some things that need to be cleaned up. It’s overdue for a refresh.

Do you mean that you’re working on a reissue of Damn the Machine?

That is correct. The book will be reissued, although that word should be used lightly. I don’t foresee it being drastically different from the original. I’m simply cleaning a few things up—that’s all!

How difficult was it to get in touch with Karl-Ulrich Walterbach? Did he see it as a way to justify some of his actions after years of controversy around his name?

Karl was very easy to get in touch with. He started a blog around 2010 or 2011 to promote Sonic Attack, his then-new management company. I received a promo of one of his bands (the name escapes me) and felt compelled to contact him for an interview. We probably spoke for about an hour, and it was clear that Karl was a guy with lots of thoughts about the music industry and his bands—he just needed an outlet. In early 2014, I approached him with the idea for the book, and he agreed. I’ll give Karl this as well: He was also perfectly fine with me interviewing all of his bands, knowing that they did not have a high opinion of him.

I’m not sure whether Karl saw Damn the Machine as a way to justify his actions or if he just wanted to share his experiences and vent. I believe it’s the latter. Karl was, without a doubt, a talented A&R man and played a key role in shaping the European metal scene. Some of his business tactics have long been questioned, and the book served as a platform to discuss them.

Bands talk both good and bad about Karl. How did you manage to separate your professional attitude from a subjective point of view? We know a lot of shitty stories about how bands got in regrettable situations paying no attention to their contracts (Amorphis, Lake of Tears, Obituary, for example), but it’s always a double-edged sword, and the story of Katatonia’s debut album and No Fashion Records is another example, as the label owner was in a far worse position. Is it possible for labels’ owners to stay supportive and gain some profit at the same time?

I believe it’s possible for a label owner to stay supportive while making a profit. However, the 1980s were a notoriously harsh time for record contracts, and most bands were eager to get signed. Of course, no one forced these bands to sign a contract, but, as you said, it’s a double-edged sword: either they hired a lawyer who likely warned them not to sign, or they signed and faced the consequences later. I think we know which choice most bands made.

From Karl’s perspective, he was primarily a businessman. He was very honest about that. He wasn’t like Brian Slagel—a guy who had good relationships with most of his bands. Many of the Noise bands saw Karl just as that: a businessman, and nothing more. That certainly helped me when I was writing the book.

Can you name some other examples of labels that managed to keep the same enthusiastic and honest approach as Metal Blade did? By the way, do you think there’s a need or a chance to write a book about another label? Hammy Halmshaw’s Peaceville Life proved to be a good reading, as well as Brian Slagel’s memoirs.

Nuclear Blast, Century Media, SPV/Steamhammer, Season of Mist, Relapse, and the aforementioned Peaceville are some of the first that come to mind in terms of longevity and reputation. Metal Blade certainly stands out because of Brian Slagel—he’s one of the most influential figures in metal and deserves a lot of credit for discovering a lot of legendary bands and also championing the style when few would. And, yes, more books about metal labels would be great. It would be cool to see a real down-and-dirty book about Earache. Digby released his own Earache book. It would be even better to have one that goes into detail about all of the relationships he had with his bands.

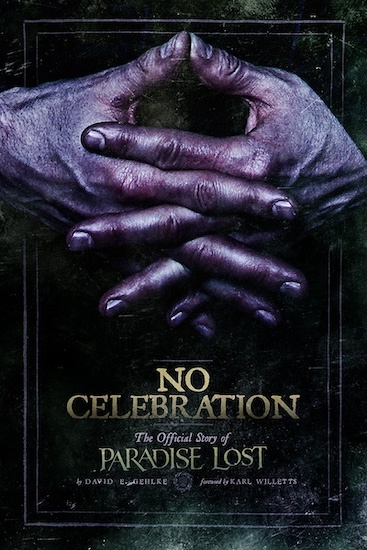

From my point of view, Paradise Lost wasn’t an obvious choice as a topic for an American writer, as they failed to create a reputation in the US when they had a chance. How did the band’s popularity change during the years?

Paradise Lost’s popularity in Europe will always surpass that of the US. They’ve openly admitted they missed their chance to establish themselves as a regular touring band here in the mid-1990s, although some of that can be blamed on Music for Nations, which was going through a restructuring at the time. They definitely have fans here—including myself. The timing on this side of the pond just never really worked out. As they approached their 30th anniversary, I suggested the idea of a biography to Albert Mudrian at Decibel. Fortunately, Albert, like me, was also a huge PL fan and was able to connect me with their management. As it turns out, they were interested in having someone tell their story, and we hit the ground running in 2018.

I know that it sounds a bit naïve, but did No Celebration’s release raise people’s interest in Paradise Lost? I bet that such a book couldn’t appear unnoticed.

The book on PL certainly helped, although they were already a legendary band. The book simply told their story and shed some light on things that people may not have known. I think they’re one of the greatest metal bands ever.

I suppose that it wasn’t easy to organize all the interviews’ sessions with them. How was this problem solved? Who was most helpful in their crew?

We had to get creative to conduct the interviews for the PL book because of the time difference, since an ocean separates us. We made it work, though, and I’ll give the band a lot of credit for being so flexible and willing to speak with me. They were all helpful, although I probably spent the most time with Greg Mackintosh since PL essentially runs through him. He was the most hopeful, since I often used him as a barometer for whatever topic needed exploring in the book.

They were a joy to work with—completely unassuming guys with zero pretense. Plus, as anyone knows, they have a tremendous sense of humor. I love how self-deprecating they are, which may be one of the many reasons why they’ve been so successful. They don’t take themselves too seriously, although they are deathly serious about their music. I’m still in touch with the PL guys and often remind them how much I miss talking to them regularly.

Paradise Lost succeeded in getting a few good contracts which led to a very strange period of their career. Did you try to get in touch with representatives of their former “big” labels to discuss those years? Was it possible?

We found a few people from the band’s major label years to contribute, although the passage of time and the fact that PL wasn’t a priority act probably limited their contributions to the book. In the late 1990s, PL being on a major label actually made a lot of sense. They had gone as far as they could on Music for Nations, and with their deal with them fulfilled and EMI ready and willing to give them a bigger budget, it was a natural transition. Host and, to a lesser degree, Believe in Nothing, are strong albums. For whatever reason, PL never quite managed to reach the next level. Oddly, they probably could have if they had decided to stick with the style of Icon and Draconian Times.

Are you usually interested in bands’ lyrics? Paradise Lost’s texts are something with which I struggled for years, and the only thing I missed reading in No Celebration was Nick’s comments on his lyrics. Did you seek his assistance to decipher it?

We probably could have explored Nick’s lyrics for No Celebration more deeply. It was likely just a matter of my not asking enough questions about them. He’s usually pretty open when you inquire about his songs—I did get explanations on a few tracks, but nothing too detailed. I think he’s an exceptional lyricist who doesn’t get enough recognition for his talent to craft some compelling melodies. Additionally, his growth as a singer is impressive. He started as a death metal vocalist, learned to sing cleanly (while going through his James Hetfield “phase”), then became a quasi-pop crooner, and eventually returned to death metal. He’s one of the best to ever do it.

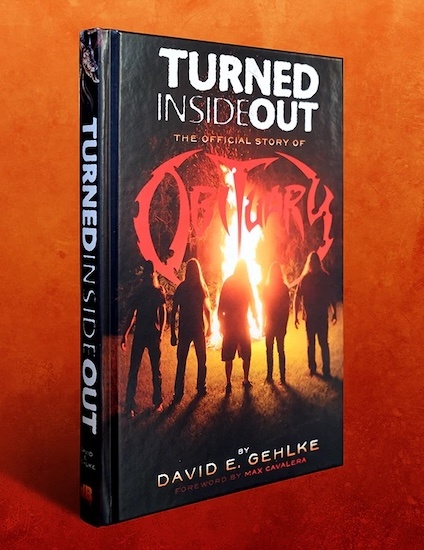

Obituary’s biography Turned Inside Out is complete and in-depth research. I bet that no stone was left unturned while you searched for information. But the story of the Tardy brothers lacks, typical for stories of that kind, the aroma of hangover and the savage joy of booze. How could it happen? Do you see their lack of interest towards revelry as their feature, as many bands from those years didn’t tend to avoid such simple pleasures like alcohol? I can understand it, but I was surprised to some level.

The Tardy brothers are very straightforward people, and this trait carries over into their music and how they run their business. I think it’s a commendable quality to have. At their core, John and Donald (along with Trevor, Kenny, and Terry) are honest, diligent, hardworking individuals with little patience for drama. What you see is what you get with Obituary. That’s part of why they’re so likable and, at this stage of their career, one of the most resilient death metal bands.

Of course, such qualities don’t always make for an exciting story, but the central theme became how hard work, staying true to your vision, and surrounding yourself with good people can take you far. It also helps that John is one of the best death metal vocalists ever; Trevor writes some of the heaviest, most brutal riffs out there; and Donald is an incredibly underrated drummer. There’s no secret to Obituary’s success other than their consistent dedication to these principles.

Obituary proved that good lyrics aren’t a necessary element of success. Do you care if a song you like has any extra meaning besides the energy the band put into it? Can you give some examples?

Obituary made it pretty clear from the start that John Tardy’s vocals were like an additional instrument and that his lyrics—whether they were enunciated or not—were not to be considered a focal point. The idea of someone at that time not even using real lyrics was revolutionary! That said, I’m actually a pretty lyric-and-vocals guy, so whenever the song in question has a deeper meaning, I’m in favor. You still can’t deny what a tremendous death metal singer John is. He’s easily in the top-5 for that.

Indeed! And what are the other four in this rating?

In no particular order: Martin van Drunen (Asphyx, Pestilence), Frank Mullen (Suffocation), Glen Benton (Deicide), and Travis Ryan (Cattle Decapitation).

The Scott Burns Sessions was published in Russian not long ago. How good are things in this field? What is your most popular book taking into account translations in foreign languages?

I’m not sure which of my books is the most popular in terms of translations. PL might be the most popular because of their strong European and South American fanbase. Currently, it’s been translated into five different languages, which has been a thrill for me. I’m hopeful more translations will happen for Scott’s book. I know a few are in the works.

Books are an old-fashioned format nowadays, the runs are low, and we can compare this situation with the decline of people’s interest towards CDs. What do you think about YouTube interviews, etc? Have you ever thought about switching to this format as a journalist? Do you watch video reviews and interviews or do you prefer to read them when it’s possible?

I do watch video reviews and interviews. Getting in front of the camera and expressing one’s opinion capably is a skill worth developing, and I commend those who are willing to do so. Video interviews are particularly interesting since you get an unfiltered, unedited view of the conversation, and sometimes those are really compelling. I’m pretty camera-shy and would much rather continue with the written word. I don’t think anyone is particularly interested in seeing me in front of the camera anyway!

I can imagine that the amount of effort you put into each book hardly pays off. How often do you think about completing this labour and start enjoying a simple life?

Part of the enjoyment in writing books is the work. I don’t see it as “work,” though. Perhaps that’s why I like writing books so much. This is a terrible cliché, but it’s true: The reward is the journey, especially when you get to meet all sorts of great people along the way. Maybe when I’m older, I’ll slow down and enjoy a simpler, more relaxing lifestyle, although I think my life is fairly relaxed. Hopefully I don’t jinx myself!

Can you name a project that you declined because it would cause only losses? Can you allow yourself to put your energy and time into something that won’t pay off in the end?

I don’t know whether I’ve turned down a project, actually. In most cases, I have pitched the idea. Writing books about metal is not a profitable endeavor—most of us do it for the love and passion we have for this style of music.

So… Born Human… Chuck Schuldiner was a pioneer of death metal, Scott Burns was a pioneer of death metal production, and Paradise Lost were the ones who invented death-doom (although I need to check if it’s true, because the Dutch scene already had similar stuff at the same time, and let’s keep in mind Dream Death). For us, each of these events is historical. I mean that the cultural significance of each of these cases is huge. Yet how do you see it objectively in terms of relatively modern culture and the music business as well?

I’m not sure if any of these topics have an impact on modern culture or the music business at large. Metal is such an isolated scene, which is probably how many of us prefer it. While a great deal of objectivity has to come into play when writing these kinds of books, the undeniable fact is that I’m a huge PL, Chuck, Scott Burns, and Obituary fan. Otherwise, I probably wouldn’t have pursued these projects. The one element that ties all these subjects together is the music business. PL, Chuck, Scott Burns, and Obituary all had their own stumbles in the industry and learned difficult lessons along the way.

Ian Christie began writing a biography of Death almost 15 years ago, as he admits in the foreword to Born Human. How did you end up getting along? Was there any competition between you?

No competition whatsoever! Ian is one of the best metal historians around and a fantastic person—we had several conversations during the writing of the book, and they were always a lot of fun since Ian is such an encyclopedia. I had faint knowledge that he and Albert had started their own Chuck bio in 2010, but figured, since so much time had elapsed, they would be fine with me taking on the project. Thankfully, they were. Both of them were incredibly supportive, and I’m quite lucky they were a part of the endeavor.

It’s not a secret that Chuck was totally dedicated to music and was a difficult person at the same time; it’s not a secret, but you decided to stay true to history. I appreciate it not because of the anticipation of controversies or scandals following some of his releases, but because of this approach itself. It’s physically difficult to read some polished authorized biographies. How difficult was it to approve this approach with his family and his former colleagues?

Transparency and honesty were the most important aspects throughout the writing of Chuck’s biography. I made a point of keeping his family informed of the book’s progress whenever I could. That meant if I learned something new about Chuck or was told something potentially controversial, I informed them. It also meant that if I was put in touch with someone from Chuck’s past who might not have the kindest view of him, I let them know. I didn’t want to keep anything from them. That was done in part because they’ve had some issues with the people who previously managed Chuck’s catalog and intellectual property, so I wanted to make sure they were comfortable with what was going into the book. The family did indeed review the book and made some updates—nothing significant; actually, they requested a few items be added. It was a really easy, fun experience with the Schuldiners. I can’t say enough good things about them, considering how much goes into maintaining Chuck’s legacy.

As I understand, Chuck’s family was totally supportive of this project. Was it possible to do the book without them? How much would it lose in weight?

It would have been very difficult to do the book without Chuck’s family. If the book were to solely focus on his career in Death, then, yes, it may have been doable. Since it was designed to be about his entire life, his family was critical. As it turned out, they were very supportive of the project and were of tremendous assistance.

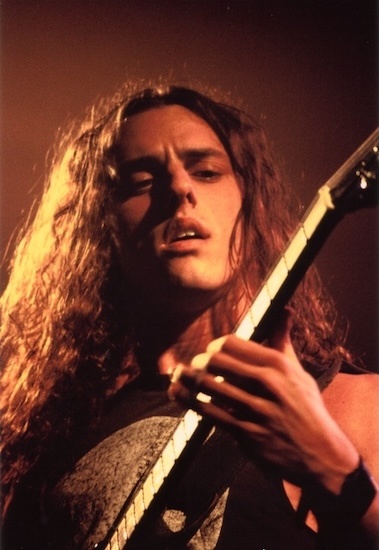

Speaking about Chuck’s peculiarities… How do you understand for yourself Chuck’s tendency to constant progression in his musicianship? Was it his gift or curse?

It was a gift, no doubt. Chuck was one of the few musicians to progress in real time. You could chart his progress from album to album; he wasn’t like Yngwie J. Malmsteen, who was a virtuoso from the beginning and has remained as such. Chuck’s musicianship and songwriting improved with each album, which made it only natural that he’d want to do new things.

Chuck had grown tired of death metal as early as 1990-1991; there was no way he was going to keep churning out albums similar to Leprosy or Spiritual Healing. He saw the limitations of brutal death metal and, to a similar degree, death metal at large. Another big factor is how much he loved traditional, old-school metal. That continued to bubble to the surface with each album and is why his albums became more melodic. It would be difficult to classify Symbolic or The Sound of Perseverance as “death metal.”

Death’s case is unique also because despite its passing through the series of metamorphoses the band didn’t lose too much in popularity. We have a lot of examples of how big bands spoiled their reputation due to changes in their core sound – some were justified later, some didn’t succeed. But Chuck found the balance somehow, and people dug it most of the time. Didn’t they?

Death is certainly one of the exceptions here—agreed. Chuck’s evolution from Scream Bloody Gore to The Sound of Perseverance is massive. He definitely lost some fans along the way, especially those who preferred the more brutal and straightforward material on Scream Bloody Gore and Leprosy. He also picked up quite a few fans starting with Human and beyond. That’s perhaps one of the more unique things about Death: Their catalog has such a variety of backers. You can ask ten people to name their favorite Death album and it’s likely you won’t get the same answer twice.

Which of Death’s lineups do you see as the most effective in matters of teamwork?

That’s hard to answer. While Chuck was the primary songwriter, his bandmates’ contributions cannot be understated. The Human lineup often gets the most nods for the spirit of “teamwork.” Chuck, Paul Masvidal, Sean Reinert, and Steve Di Giorgio came together in a relatively short period of time under difficult circumstances—Chuck had fired Terry Butler and Bill Andrews (technically, they quit), and he was under a lot of pressure because he had bailed on another tour. Human was Chuck’s “prove it” album, and Death delivered a death metal landmark.

While it’s not the first technical/progressive death metal album, it’s one of the most popular, and a lot of that has to do with the lineup and Chuck’s willingness to let his bandmates shine. Really, Reinert, Masvidal, and Di Giorgio had the green light to play whatever they wanted—within reason. Chuck only pulled them back when it was absolutely necessary, which explains why their stamp is all over the album. It’s a shame that the lineup lasted only one LP.

Were there ex-Death members who refused to speak about the band?

Every former Death member I contacted agreed to speak for the book. Now, the only person I couldn’t get in touch with was Eric Brecht, who drummed for the band in the mid-1980s. We tried every avenue possible to find Eric, but to no avail. Then again, I’m very happy we had such a high success rate in getting people to speak for the book.

Chuck said that the key mood of his music is positive, or like that, and of course it conflicts with the nature of music he composed and performed. How do you solve this issue for yourself? Do you feel the same?

It’s true that Chuck wanted to surround himself with positive people since his experiences with the music industry were often so negative. At his core, Chuck was a positive person—I don’t think he ever thought the music business would be so unforgiving when he signed his first record contract in 1986, when he was 19 years old. The business is, perhaps, the one thing Chuck hated the most (touring would be a close second), and it’s easy to see why. He was constantly under the microscope since he was the “Godfather of Death Metal” and endured countless lineup changes. The attention on him was relentless. I don’t know how he put up with all of it at such a young age. Certainly, a lot of us would crack under that kind of pressure if we had to go through it in our 20s.

The story with the constant delay of Control Denied’s second album When Machine and Man Collide seems to be overcomplicated, so how would you sum it up? Was everything said in the book? Or is there some update on this topic?

The book goes fairly deep into why the second Control Denied album has been delayed. The reasons for its delay are numerous, and there is a bit of a dark cloud hanging over it—I don’t think any of the remaining guys would dispute that. They now have to figure out what to do about the lead singer spot since Tim Aymar passed away, so there’s another element of uncertainty injected into the situation.

It’s not for the lack of wanting to get it done, though. Shannon, Steve, Richard, and Jim Morris all feel an obligation to Chuck to finish the album, and I think they will, based on what they told me. It’s more a matter of finding the right time to get everyone together and to do it in a manner that properly honors Chuck and does the songs justice. Chuck did finish four rhythm guitar tracks in Morrisound—those can be used. The tracks he recorded at home after his brain cancer returned remain the big question mark. I’m not sure what they will do with those recordings. It’s not for a lack of trying, and I give those guys a lot of credit for wanting to finish the album 24 years after the fact.

Now, after all the work you’ve done, what are the turning points in his career that you would pick up as crucial ones?

The death of Chuck’s older brother, Frankie, changed everything for him. It completely shaped his life from that point forward. It’s interesting to listen to a song like “Symbolic,” where he talks about wanting “innocence” and returning to simpler times. The period before his brother’s death was exactly that, and I don’t know whether he ever found a similar sense of peace. Chuck had a very tough time after his brother died, and it wasn’t until he discovered KISS that he found happiness. Then, thankfully, he tried playing guitar again, which eventually led to him forming Mantas, then Death.

David, you have a very unique niche taking exciting themes to investigate. Do you fear that someone will get ahead of you and write a book on a theme that is dear to your heart and you feel ready to work with?

We’re fortunate to live in a time where metal’s illustrious history is coming to life via all sorts of books from all sorts of excellent, talented writers. I don’t really think about someone writing a book about a topic before me. It hasn’t happened yet, although I’m sure it will at some point. Whatever the case, it’s a great time for metal books. There are so many fascinating subjects, and the scene has a wide array of writers who can tell these stories. I buy pretty much every metal book that comes out.

How do you manage to find balance between family, work, and writing?

Ah, that’s a good question. I’m not sure. I have a wife and a daughter—they come first. And, of course, I don’t write books for a living, so it’s a matter of finding time to do it. I try to devote at least one hour a day to whatever book I’m writing. I figure that as long as I do that, I will stay on track. I don’t mind the work and enjoy every step of the process of writing a book. Above all else, it’s a thrill to work with such great people at Decibel and most certainly, the bands who are kind enough to subject themselves to my questions!

https://store.decibelmagazine.com/products/born-human-the-life-and-music-of-deaths-chuck-schuldiner

After the Scott Burns book, David Gehlke became an author that I’ll read whatever he does without question. So excited for the Death book (for my copy to arrive, I should say, currently in the mail) and glad I was able to get his signature on my copy of the Obituary book at Metal & Beer.