(We welcome back our guest writer Lonegoat, the Texas-based necroclassical pianist behind Goatcraft, whose latest album Yersinia Pestis was released earlier this year by I, Voidhanger.)

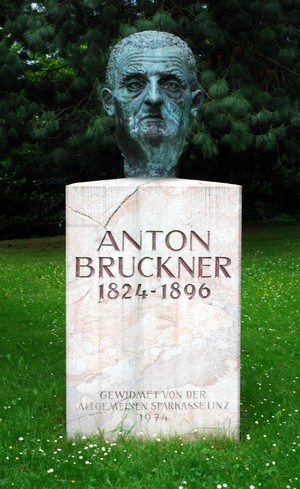

I’ve decided to feature one of my favorite symphonies for my second entry for No Clean Singing. It is metal as far as spirit is concerned, which I will attempt to delineate here. My next entry will be about an actual metal release, so you won’t have to worry about me spamming classical music at everybody here all of the time. I will first talk about Bruckner-the-man before Bruckner-the-composer.

Of Bruckner’s numerous quirks, what struck most people as odd was his obsession with death. He kept a photo of his mother’s corpse, and when Beethoven and Schubert’s graves were exhumed for their remains to be relocated, Bruckner was there to fondle their skulls. Nobody’s quite sure why he was infatuated with death so much, but his music might shed an insight on it, as it often goes from heavenly beauty to demonic predation. Other than this macabre quirk, he would also propose to teenage girls/young women, even while he was elderly. Most men are attracted to younger women so this isn’t that bizarre.

To enjoy Bruckner’s 9th in its fullest capacity is not something that immediately comes for most people. First, it is important to understand Bruckner’s main idiosyncrasy with how he drew a very broad landscape and developed it over long durations. He would compose first by drawing out all of the bars, then filling in the melodies and later the instrumentation. This is a rather unorthodox practice for a composer, but it can be said that Bruckner was an architect on manuscript paper in this regard, perhaps holding mathematical weight in addition to its musical gravitas.

Another noticeable Brucknerian trait is his use of arpeggios on the bass staves in many of his works. Some musicians complain that it’s too much repetition for them to perform, often shifting the same patterns to different notes, but, as previously stated, Bruckner worked with long expanses, and elements like this help illustrate the texture for his symphonic world-caverns.

For Bruckner’s 9th, it’s also important to see where he was at in his life. He knew he would die soon, and he suffered from poor mental health while he wrote the symphony. As such, there’s an air of dysphoria intermeshed with raw power throughout the first movement underneath its solemn exterior. It requires endurance, but when the expanse comes to a closing, it’s tied into a nice bow with one of the most powerful climaxes ever written, utilizing numerous voices in contrapuntal unison, which hoists the listener beyond the world of phenomena. This moment of closing is a high apotheosis of absolute music; a supreme end-in-itself.

Many people have correlated the turbulent music of Bruckner to heavy metal because much of his music is heavy-natured. New “evidence” to bridge Bruckner closer to metal has surfaced over at Classic FM (here), which exhibits the 9th’s second movement in juxtaposition to Metallica. The second movement does seemingly have a metal riff motif, however it is metal in spirit more than composition. Bruckner’s 9th is synthetic a priori whereas Metallica is analytic a posteriori.

Unfortunately, the third movement was not meant to be the final movement because Bruckner died before he could complete the finale. The third movement portrays some of the most beautiful music ever written by Bruckner, then it’s followed by a sonic vortex which beholds a frightening power. Then, after that passes, it is resolved by a faux conclusion… Fuck the demiurge for letting Bruckner die before he could finish the 9th!

Where was he from? This was pretty good. It actually got heavy too at about 22:00. I haven’t listened to classical music in quite some years. I like it sometimes. I have always wondered something about classical. Why is it all old? Meaning, aren’t there contemporary composers? It seems to be mainly people playing “classics” from last century. Yet Bruckner and Vivaldi, Bach, etc etc were not playing songs by composers that preceded them by 100 years. They were playing current stuff (at that time). May be a stupid question for someone more familiar with classical music.

I enjoyed your article, but you lost me here: “He would compose first by drawing out all of the bars, then filling in the melodies and later the instrumentation. This is a rather unorthodox practice…” What’s a “bar”? And why was his approach unorthodox–how did others do it differently?

Re: “What’s a ‘bar’?” —

A bar, in music, is defined here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bar_%28music%29